The women in our group walk clockwise laps around two round ovoo, sacred cairns, spraying them with tetra-packs of milk. Unmistakeably mammary in shape, the ovoo are coated with layer upon layer of milk that has baked under the desert sun to form a thick, fetid crust. From a distance, it looks like sand. The smell and heat make a nauseating combination, and the wind blows our milky offering back in our faces.

We are half an hour’s drive from Sainshand, a small city in the Eastern Gobi. Two Australian volunteers living in Sainshand have very kindly put us up for the weekend, giving us the chance to explore both the town and the nearby Khamaryn Khiid monastery.

Sainshand has a frontier town feel, complete with Vegas-style lighting and a neon sign welcoming visitors to town. The monastery, on the other hand, feels so deep in the desert it is almost unfathomable that anyone could live out here. There is an underground spring, which explains how people and livestock were able to survive. The monastery was originally founded in the 1820’s by Danzan Ravjaa, destroyed by the communists i n the 1930’s, and rebuilt around 25 years ago. Ravjaa is reputed to have been the second most intelligent man in Mongolian history: a Lama, poet, and playwright. (Chinggis Khan is, of course, numero uno.) Near the monastery is the Shambala Energy Centre, a sacred site ringed by 108 white stupas. Pilgrims come to make offerings and lie on the warm earth to soak up good energy. We scatter millet to give thanks for good things past, present and future. We throw cups of vodka in the direction of the sacred mountain Bayanzurkh Uul and make wishes, the only proviso being that we can wish for neither health nor wealth.

n the 1930’s, and rebuilt around 25 years ago. Ravjaa is reputed to have been the second most intelligent man in Mongolian history: a Lama, poet, and playwright. (Chinggis Khan is, of course, numero uno.) Near the monastery is the Shambala Energy Centre, a sacred site ringed by 108 white stupas. Pilgrims come to make offerings and lie on the warm earth to soak up good energy. We scatter millet to give thanks for good things past, present and future. We throw cups of vodka in the direction of the sacred mountain Bayanzurkh Uul and make wishes, the only proviso being that we can wish for neither health nor wealth.

We visit caves used by Danzan Ravjaa and his followers for meditation. One of these is a long narrow tunnel, and to crawl through symbolises rebirth. A young Mongolian couple inch through on their stomachs with a newborn baby. We follow, taking it in turns to squeeze through the rocks. Some of us opt for breach deliveries. Matt comes out head first, but ends up with a bruised skull to show for it.

Although the men weren’t allowed to join in the earlier milk spraying ritual, they are not left out entirely. We drive to the foot of Bayanzurkh Uul, which in true Australian style we re-christen on account of the summit only being accessible to men. Our driver makes it very clear that the women aren’t to climb to the top, emphatically making a cross with his arms. We stop in a shelter half way up and watch goats sunning themselves while the men continue the climb. I could make all sorts of wild assumptions about the secret men’s business happening on the mountain top, but in the interests of fairness I have asked Matt to fill in the blanks here. He says:

‘We shuffled slowly up the mountain, four weedy boys lugging a backpack containing nearly half a bottle of vodka as a gift for the Buddhist deities. The weight of the bag—it must have been nearly two kilograms—and gravity combined to make the journey a tough one. Our legs burned, we wheezed, my glasses fogged up. We crested a ridge, and suddenly we were there. There was a large pile of rocks covered in presents for the deities—a charred animal corpse, litres of vodka, sky-blue prayer scarves and small piles of lollies.We thanked the deities for our survival and threw our vodka into the air in thanks. Then I felt something stirring. I heard a sound not unlike a combination between a truck engine, gorilla grunts and a power drill. My muscles bulged, my breathing slowed and my heart rate settled at a manly 35 BPM. I felt a strong desire to have a discussion about carburetors. I looked around and saw the others were now men too—boys transformed. After a quick game of rugby and some manly hugs, we strode back down, our gait necessarily a little wider than before. Thank you Mongolia, for making a man out of me and my bros.’

Perhaps the goat watching was a better option after all…

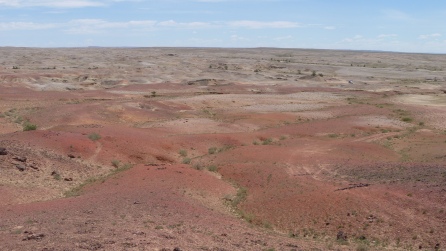

Amongst all this human birth and rebirth, we find the fossilised spine of a dinosaur, its vertebrae still positioned in a graceful arc. We see the petrified stumps of trees, and try to imagine that a forest once grew in these wide open plains.

On the way back to town, we pull over to watch a large herd of Bactrian camels and their calves, who are quite sensibly crossing the road at a signposted crossing. One pushes his neck out and bares his upper teeth at us, but the rest amble slowly away. Later, we see a small herd of sturdy little horses and foals.

Getting to and from Sainshand means a trip on an overnight train. The first leg of the journey is uncomfortable—sticky hot and airless in our compartment. We are serenaded by a woman who is rolling drunk despite alcohol not having been available for sale for three days (due to the Mongolian election and laws preventing the sale of alcohol on the first of each month).

The return leg is far worse.

Tickets for coupe class, which would at least have allowed everyone their own bunk to sleep on, are sold out. We end up in a seated carriage for the nine hour overnight journey, packed in with families, soldiers in combat fatigues, and sweaty men who have rolled up their t-shirts and are showing off white bellies. It has been 37 degrees outside all day, and the mass of bodies means it is no cooler inside the train. Matt plays cars with a small boy, who brings gifts of salami. By now I have exhausted my supply of Shambala energy, and am wondering whether the 17,000 tugrik difference between coupe and second class tickets should have been spent on a bottle of Chinggis Gold vodka. In a desperate bid for sleep, I try to do as the locals do and stretch out on the baggage shelf a foot below the ceiling. The conductor lets it pass for an hour before tapping insistently on my foot and demanding I get down. The train rolls on painfully slowly, but eventually, 28 stops later, we have swapped the desert for the rolling green hills that ring Ulaanbaatar. There is just time for a coffee before the morning language lesson begins.

Wow! What an amazing part of the world – so much diversity on this planet Earth that we have absolutely no idea about – unless you have rellies who seek out the experience and share! keep the visual/mind pictures coming, Kate and Matt xx

LikeLike

So great to read about your adventures – sounds amazing (and exhausting).

Keep these coming!

Einat & Bash

LikeLike

It is somehow reassuring to know that the gods like lollies and vodka. It gives them an approachable, human feel that was always missing from Apollo in his sun-drawn chariot, or the chap who wrought the foundations of the earth.

Camels are OK but I’m still hanging out for a genuine mongolian marmot. Keep looking.

Finally, a free spell check. A breech birth has 2 e’s. You could give a whole new meaning to King Hal’s exhortation at Agincourt (Once more into the breAch, dear friends…).

Keep the blogs coming.

LikeLike

I am, of course, mortified to have committed such an egregious spelling breach!

LikeLike